I have just finished watching the fantastic documentary about Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo and its epic 2016 match against World Go Champion Lee Sedol. You can find it, here.

Essentially, Lee Sedol, winner of 18 world Go titles and widely regarded as one of the best Go player ever to live, shockingly lost the first three matches against AlphaGo, the algorithm developed by DeepMind. Lee Sedol won the fourth match by playing an incredible stone at move 78. AlphaGo took the fifth and final match, winning the contest 4-1.

“I thought AlphaGo was based on probability calculation and that it was merely a machine. But when I saw this move, I changed my mind. Surely, AlphaGo is creative.”

Lee Sedol

Winner of 18 world Go titles

Go is widely regarded as the most complex two player game and AlphaGo’s victory was seen by many as the first point of AI’s true ascendency over humans. The Go match provoked comparisons with Garry Kasparov’s Chess match against Deep Blue in 1997. Deep Blue won that match 3.5–2.5, the first time a computer algorithm had beaten a professional chess player in a timed tournament. It caused a sea change in our perception of computer programmes’ abilities. Gary Kasparov gave an excellent Talk at Google about the match and future of AI, which is available here.

“Back then we had the problem of engines cheating using humans. Now we have the problem of human’s cheating using engines.”

Gary Kasparov

former World Chess Champion (1985–2000), speaking about his match with Deep Mind in 1997

Winning at Go was the next frontier for computer algorithms. Because there are so many potential configurations of pieces on the (typically) 19 x 19 board, attempting to assess the best passage of play by brute force ‘crunching’ of all possible scenarios is simply not possible. Further, when playing Go it is sometimes not obvious, even to top human players, why a move is ‘good’ – intuition is very important, particularly because seemingly innocuous moves early in the game can have unseen ramifications later on.

A new way to play

AlphaGo played in a way which surpassed human understanding. In particular, move 37 of Game 2 was so surprising it caused experts to reconsider hundreds of years of received Go wisdom (see the graphic below). You can watch a great 15-minute summary of Game 2 by some top-level professionals, here.

Speaking at a press conference after the match, Lee Sedol said “AlphaGo made me realize that I must study Go more.” Players were subsequently given access to AlphaGo’s playing data. Interestingly, it has been proved (using AI!) that, since being exposed to AI play, humans have developed significantly improved strategies of play.

One of the particularly interesting insights from the Lee Sedol match was that AlphaGo does not care about its winning margin. Winning by a single point is as good as by a landslide. This is in contrast to human players, who tend to use winning margin as a rough proxy for chances of success. While in most cases this proxy is reasonable, AlphaGo’s method is more accurate, particularly in fringe cases.

AlphaGo Explained

Watching this documentary led me down a rabbit hole of understanding how AlphaGo works, and the increasingly sophisticated, and autonomous, game-playing algorithms developed in recent years by the team at Google DeepMind.

AlphaGo is a composite algorithm. It uses a Monte Carlo tree search to find its next move (you can read about it here). In summary, first, the team at Google DeepMind trained an artificial ‘neural network’ (a deep learning method) using human data. This was known as the “policy network”. Then the team had AlphaGo play itself millions of times, while they tracked which moves were more successful. Finally, the moves from the matches in the second stage were used to train a second neural network, known as the “value network”.

In-game, AlphaGo used a combination of the “policy network”, to select the next move to play (based on the probability of success it assigned), and the “value network”, to predict the winner of the game from each position. This meant that AlphaGo could both assess how a top human-level would be likely to play, and that its learning came from both human and inhuman sources.

For instance, AlphaGo analysed its move 32 in Game 2 (mentioned above), as a move which only one in ten thousand human players would make. Yet it made it anyway. Similarly, (and in a pleasing moment of symmetry) Lee Sedol’s fabulous move 78 in Game 4, which ultimately allowed him to win that match, was assessed by AlphaGo as another one in ten thousand move. Only a player as exceptional as Lee Sedol could have found it and, in that game, eke out an advantage against AlphaGo.

That said, any small weaknesses have long since been patched in more efficient, and generalised, algorithms.

AlphaZero

In 2017, Google DeepMind released AlphaZero (Science journal paper here, DeepMind blog here). Instead of being trained on matches with amateur and professional players, AlphaZero learnt solely by playing against itself. Armed only with a knowledge of the rules of the game, and starting from completely random play, AlphaZero quickly surpassed the performance of all previous players (human and algorithmic).

Because it was only taught the rules of the game, and no pre-existing corpus of data was needed for reinforcement training, the AlphaZero model was remarkably flexible. It discovered new and unconventional strategies and creative new moves. Its radical and inventive style of play in Chess (the subject of the fascinating book, Game Changer) shows how it is changing how humans think about the game.

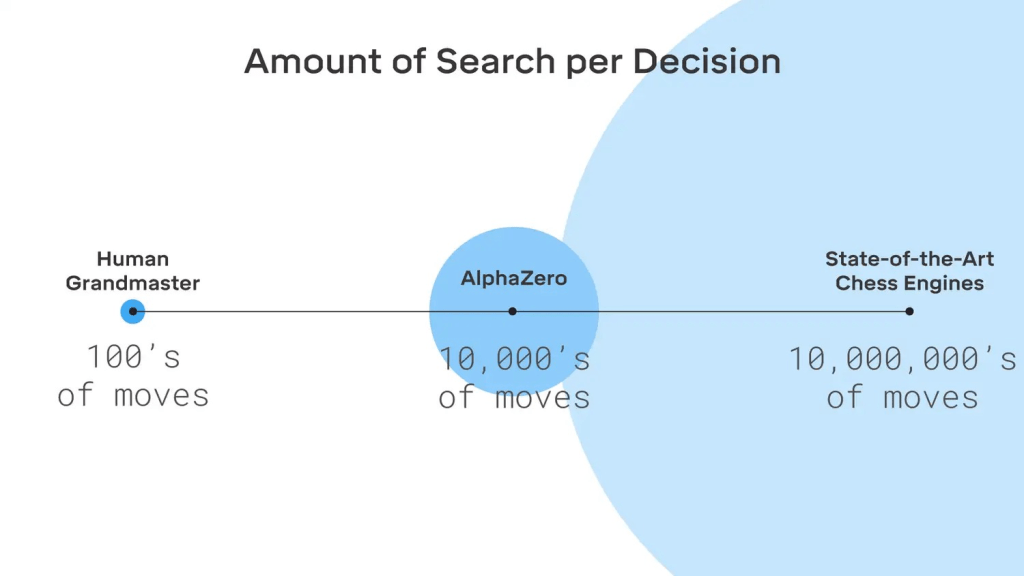

AlphaZero is also much more efficient than previous versions. Writing about AlphaZero, Google DeepMind said: “For each move, AlphaZero searches only a small fraction of the positions considered by traditional engines. In Chess, for example, it searches only 60 thousand positions per second, compared to roughly 60 million for Stockfish [one of the best similar algorithms].”

This algorithmic efficiency is another reason AlphaZero was such a breakthrough. Instead of using random ‘coin-flips’ (“roll-outs”) to assess the viability of different branches of the Monte Carlo Tree search (see image below for the search process), as previous versions had, AlphaZero instead uses its own neural network to assess each branch’s viability. This also means it uses much less energy than similarly strong models.

MuZero

Google DeepMind have since upped the ante with the incredible MuZero (DeepMind blog post here), which has mastered Go, Chess, Shogi, and the visually complex game Atari without pre-existing knowledge of the rules.

Not only does MuZero not need to know the rules of the game, it can also analyse the game-playing environment. Chess, Go and Shogi are all ‘perfect information’ games, where the boundaries of the environment are clearly delimited. While previous versions (such as AlphaZero) use varieties of a ‘lookahead search’ to plan future outcomes, MuZero instead uses ‘model-based planning’ to construct an accurate model of the environment’s dynamics and use that to plan. Previously this was too complex for algorithms to do, but MuZero gets around the limitations of earlier model-based planning algorithms by focusing only on aspects of the environment important for its decision-making process. This means that MuZero is able to master environments with unknown dynamics, to a degree never before seen in AI.

Conclusion

All of this is incredible, and clearly game-playing algorithms are coming on leaps and bounds. The possible myriad of use cases is only just becoming apparent, but already the AlphaZero algorithm has been applied to complex problems in chemistry and quantum physics. In short, this is just the beginning. To end this on a positive note, just as a rising tide lifts all boats, the improvement of human Go players since AlphaGo’s creation in 2016 shows that increasingly sophisticated and efficient algorithms will open up new and unforeseen possibilities for humans to explore.